By Richard Gwynallen

Worth Bagley Allen, Jr.

1928 – 1968

Relationship to Fawn: Grandfather

There are many places in the landscape of a family, markers along the road, crucibles of memories, places where just being there helps you think about the life of your family.

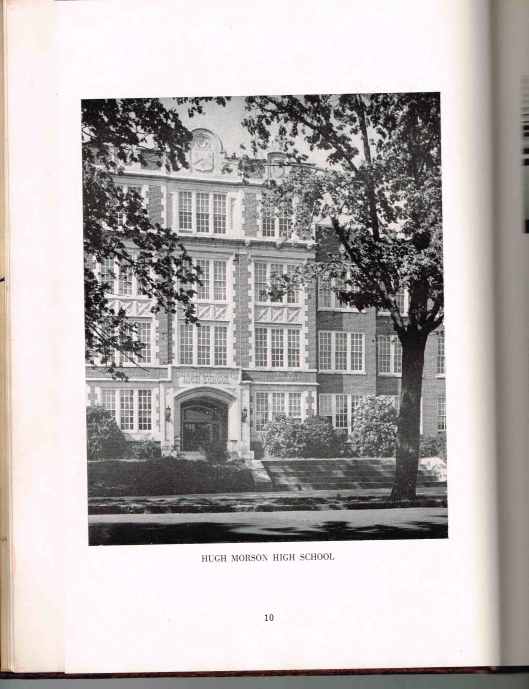

Recently my brother, Jerry, pulled out of his collection of family things our father’s high school year book from Hugh Morson High School in Raleigh, North Carolina for our Dad’s graduating year of 1945.

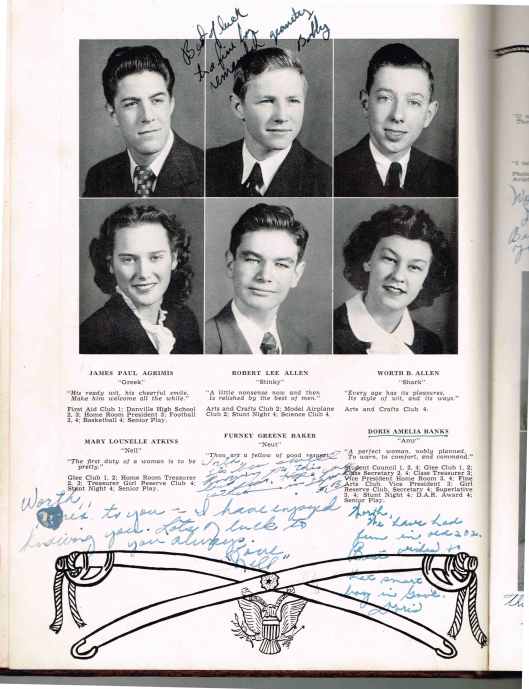

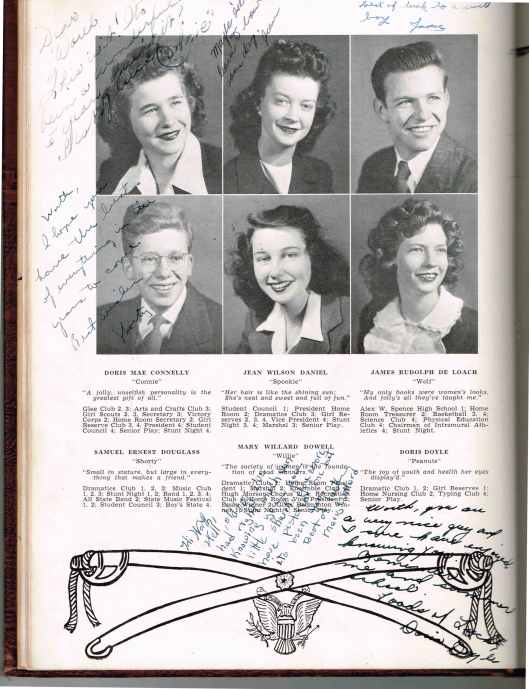

The pages are filled with inscriptions from friends as everyone’s year book of every year is filled. Our father looks young and innocent. In fact he was pretty young. He’s only 16 in the picture below. He had gone to summer school to earn enough credits to graduate out of the 11th grade. When he turned 17 that July after graduation my grandmother signed permission for him to join the Army. So, in the last weeks of World War II my father became a soldier, did his hitch, then transferred into the reserves and went to college at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, returning to the regular Army after college graduation.

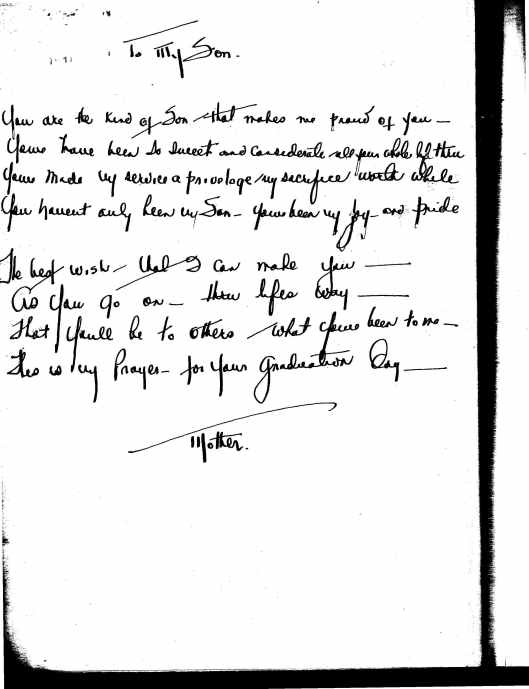

My grandmother’s inscription with her wish for her son was I thought the most beautiful thing about the book.

Hugh Morson was a high school from 1925 – 1955, then a junior high school from 1955 – 1965.

This photo was taken from the 1945 yearbook

In the early 1920s the Raleigh school system undertook the design of four modern school buildings. These were the days of segregation, so there was a white and a black high school built, the white school being Hugh Morson High School near Moore Square, and Washington High School for African-Americans on the southern extension of Fayetteville Street. In addition, Wiley Elementary School on Saint Mary’s Street, and Thompson Elementary School on Hargett Street were designed and built.

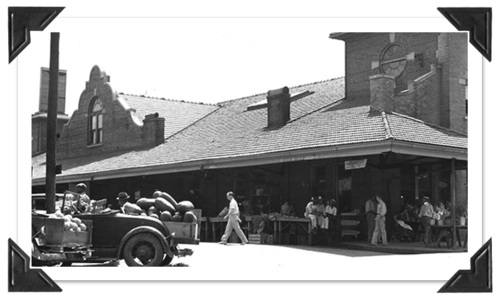

There were less than 50,000 Raleigh residents in 1945. It was the size of Medford, Oregon when our daughter grew up there. Walking distance from the school was the Raleigh City Market on Moore Square.

1940s photo

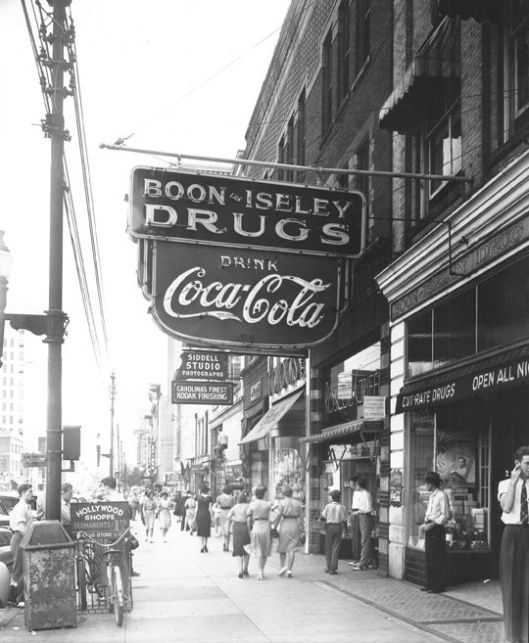

As were theatres like the Capitol at 124 West Martin Street, and the Ambassador at 115 Fayetteville Street

Finch’s opened in 1945 as a drive-in on Peace Street, where customers pulled up in their cars and gave waitresses their orders.

Only 5,000 households countrywide in 1945 had televisions. My father would have listened to the news and sports on radios like these.

It was an era of hair slicking products like Brylcreem and Wild Root

1944 poster in UK railway station

1945 poster

the debut of National Velvet

Lunch counters and malt shops

Fayetteville Street – 1940s

Lunch counter at F. W. Woolworth in the 1940s

As is evident from the pictures in this essay, it was also an era of segregation, and it would have been apparent everywhere, part of the landscape of my father’s youth. A high school for whites and a high school for blacks. Separate places to eat. When my father went to movies at the Ambassador pictured above he went in one entrance, while black movie-goers entered via a side entrance.

Referring to the growth of Raleigh from 1900 – 1945, HistoricRaleigh.org writes: “The city limits billowed to the north and west to encompass the white, middle-class suburbs developing on land once considered remote. First the streetcar system and later automobile ownership made such locations attractive in the twentieth century. Deed restrictions kept these new subdivisions segregated. Established African American neighborhoods southeast of the center of the city continued to grow as well, and early twentieth-century suburbs for African Americans were established nearby.”

But change was in the air. The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) was founded during the war in 1942, and pressure for desegregation increased as WW II entered its final months.

Growing up in the segregated South can have different effects on people. I don’t know what turned my father in his own direction, but we were brought up with the very core understanding that everyone was equal. I recall a conversation between my mother and grandmother after my father died in which my grandmother acknowledged that even in his younger years he looked at everyone the same and helped everyone when they needed it. She mentioned that once while he was in high school he spent many days helping a black family on their farm because the father had been injured. She said he was the only white man in the field and he never seemed to even think about it.

Labor unrest was also on the rise as this graduating class stepped out of school. In 1945  and 1946 4.5 million workers from every industry participated in strikes fighting against wages that were lowering. In 1945 alone, 10,500 film crew workers had struck in March, and 43,000 oil workers went out in October, followed by 225,000 auto workers in November.

and 1946 4.5 million workers from every industry participated in strikes fighting against wages that were lowering. In 1945 alone, 10,500 film crew workers had struck in March, and 43,000 oil workers went out in October, followed by 225,000 auto workers in November.

I don’t believe my father ever held a job where he would have had to strike, but once when we were traveling cross country we pulled up late a night to our hotel only to find the staff on a picket line. Despite how tired we all were he pulled away and they searched for another place with vacancies. I was told that you never cross a picket line; that it’s like saying it’s okay to mistreat people and take their jobs. It stayed with me. I never have crossed a picket line. It’s like littering. It’s instinctual. I just can’t do it.

My father walked out of high school into the military as a way of paying for his college education at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

The graduating class of 1945 was stepping out into a very different world than when they started their high school years. Women had joined the work force in droves, forever changing the role of women in economic life. And, of course, thousands had lost loved ones as war defined the entire span of their high school lives.

Shortly before they graduated the Nazi regime fell. Then in their first summer after graduating the world’s first nuclear bomb was dropped on a human population. Power most had never conceived of had been released. Then Japan surrendered and the war that had defined their high school years was over.

But the halls all these students walked day in and day out are now long gone. The demolition of a school is a sad thing to me. Even in this more mobile world, so many of our memories of our youth and of the neighborhood are bound up in the school itself. How much more so when generations of a family grew up in the same town?

demolition of a school is a sad thing to me. Even in this more mobile world, so many of our memories of our youth and of the neighborhood are bound up in the school itself. How much more so when generations of a family grew up in the same town?

Once a school in which one spent years is gone its absence is palpable.

A wonderful website called Good Night Raleigh has two articles well worth reading covering demolition of the school: The Death of a High School and ‘In Days of Auld Lang Syne’ — Chronicling the Last Days of Hugh Morson High School. I am grateful to Good Night Raleigh for many of the photos I have used in this essay.

Alumni erected a memorial for the school in 1978. The brick marker pictured above contains gargoyles that once guarded the entrance to Hugh Morson High School.

The gargoyles are visible above the third floor windows in the center section

The gargoyles now face the site approximately 275 yards southeast between Person, Morgan, Bloodworth, and Hargett Streets, the streets that bordered Hugh Morson High School.