By Richard Gwynallen

NANCY RITCHIE

1822 – 1894

Relationship to Fawn: 4th great-grandmother

Nancy Ritchie married James Murdock before 1841 in North Carolina, probably in Iredell County. The assumption about their marriage is based on the fact that their first child, William, was born in 1841.

I left this family line alone for quite awhile because we have a death certificate that shows her last name as Rickie. However, I couldn’t find a Rickie family in that area to correspond to her, and she appears in various Murdock genealogies as Ritchie. Also, there are families named Richey and Ritchie in Rowan and Iredell counties in North Carolina in the same time period of our interest. Some are of Scottish extraction, some of German.

All that seemed certain is my 3rd great-grandfather, James Murdock married Nancy Ritchie or Rickie, and they had a son from whom we are descended, John, who married Nancy Angeline Boyd. The Murdocks and Boyds were Irish and Scottish, but that was not enough of an indicator as to whether Nancy Ritchie was from a Scottish or German family.

As an amateur looking into family history I didn’t have the time to try and dig any deeper so I decided to let it sit.

A small break occurred when a Ritchie also doing genealogical work sent me a note saying that he, too, had a relationship to the Murdocks. I understand that in a family bible belonging to them (which I have not seen, but have no reason to disbelieve), Nancy, the wife of James Murdock, appears as a Ritchie, her father being identified as “John Ritchie” her mother, “Nancy”. Others the writer’s parents had contact with said that these Ritchies came from Virginia originally, Scotland before that, and that John Ritchie’s father was James. Efforts have been made to contact the original researchers, and if there are eventually responses I will update this essay.

We can say that this particular Ritchie family believes this is the accurate parentage. If this is accurate, Nancy’s parents are probably John Ritchie, son of James Ritchie and Mary Polly Keith (and known as “Long John” for reasons I do not know), and Nancy Hutchinson. An added complication is that John Ritchie and Nancy Hutchinson had two girls named Nancy Ritchie associated with their family. They were not peers as they were separated in age by 13 years. Were both girls their daughters, or was the younger a cousin they took in? If both were their daughters why were they both named Nancy? Until proven otherwise, this essay assumes that at least both lived as sisters. If our Nancy turns out to have had different parents and was a cousin to the other children of the house I feel confident that we at least have the correct family line and common immigrant ancestor.

This Ritchie family descends from Ritchie family members who left Scotland sometime between 1758 and 1770.

While this essay was principally aimed at better understanding the Ritchie family that married into the Murdock line, the Keith family of Nancy’s grandmother, Mary Polly Keith, a 5th great grandmother to me, has a couple interesting stories of its own. So, I will be elaborating a bit on the Keith family rather that give them a completely separate essay.

Ritchie Migration to the American Colonies

James Ritchie was born was born 8 May 1757 in Ayrshire, Stewarton Parish, Coayr, Scotland. I’m not sure where Coayr is, unless it is just a reference to the town of Ayr. It is believed that he arrived in the colonies with his father, Alexander. Some of his brothers either accompanied them or followed. Some researchers believe they sailed from Liverpool, England, about 1768 on The Marigold, but this is not confirmed.

Alexander was married to Margaret Wilson. We assume she died prior to their emigration because she is not referenced as being part of the emigrating family. They had eleven children. The family story is that Alexander fought at Culloden in 1746, and they became part of the large post-Culloden Scottish migration of the 1750s through the 1770s. The Ritchie or MacRitchie name is considered to be a sept of the Mackintosh clan in the Dalmunzie area of Scotland in the Highlands of North Perthshire.

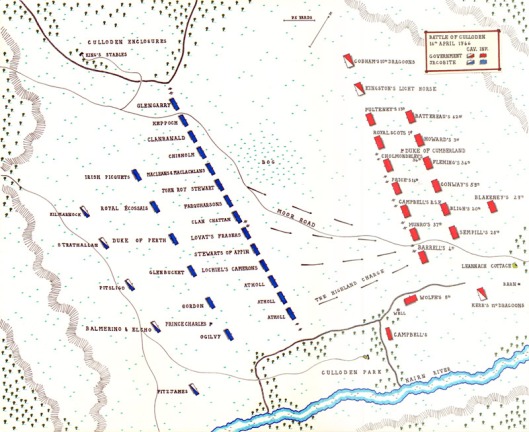

Though unproven as of yet, if the family story that Alexander was present at Culloden is  accurate, he would most likely have been part of the Mackintosh or Clan Chattan regiment mustered by Lady Anne Farquarson of Mackintosh, and led in the charge at Culloden by the MacGilllivary chief, a clan member of the Clan Chattan Confederation in which the Mackintoshes were the principle clan. I have not seen a muster role for the regiment. In the image below one can see Clan Chattan’s position on the field. They are drawn up next to the Farquarsons led by Lady Anne’s cousins.

accurate, he would most likely have been part of the Mackintosh or Clan Chattan regiment mustered by Lady Anne Farquarson of Mackintosh, and led in the charge at Culloden by the MacGilllivary chief, a clan member of the Clan Chattan Confederation in which the Mackintoshes were the principle clan. I have not seen a muster role for the regiment. In the image below one can see Clan Chattan’s position on the field. They are drawn up next to the Farquarsons led by Lady Anne’s cousins.

Position of forces at Battle of Culloden

We don’t know where they entered the colonies, though some believe they entered at Yorktown, Virginia and stayed for awhile on the James River. Given the marriage James Ritchie makes, which we will see later in the essay, this seems likely. However, his father, Alexander, is recorded as dying in 1787 in Cumberland County, North Carolina. That would imply that no matter where they entered, eventually they, or at least he, headed for the significant Scottish Highland community of the Cape Fear area of southeast North Carolina. Perhaps they had family in the area that had emigrated earlier.

James must have moved back north, or perhaps never left Virginia, because we find him married to Mary Polly Keith, in Stafford County, Virginia, the daughter of Samuel Keith and Catherine Ring.

James served as a private in the 2nd Virginia Regiment in the Revolution. He was thought to have been present at the battles of Monmouth and Kings Mountain. He fought at Yorktown along with his brother, John, and was captured.

Later James and Mary moved with more of their family to what was Burke and would become Buncombe County, North Carolina prior to 1790 when they appear in the first federal census. Also on the 1790 Census of Burke/Buncombe County are two of Mary’s brothers, Gabriel and Ruben. They all appear again on the 1800 census, but afterwards James and Mary move back to Virginia around 1801 or 1802. In 1802 James applied for and received a land grant in Russell County, Virginia in 1804. They lived beside Crane’s Creek in what is now Wise County, Virginia.

James and Mary moved on to Kentucky about 1815. James drowned crossing Carr Creek, a branch of Troublesome Creek, in Perry County, Kentucky, in 1818. It’s said he was buried near Carr Creek.

By this time they had at least six children. Mary seems to have moved back to North Carolina with her family, except for Alexander Crockett Ritchie who remained in Kentucky, and in which state his descendants still reside.

Mary’s son, John, and his wife, Nancy Hutchinson, settled in Scott County, Virginia where they appear on the 1820 and 1830 census. As I noted earlier, interestingly enough there were two girls named Nancy Ritchie in there household. One born in 1809 who would marry Jeremiah Powers, and our Nancy, born in 1822, who would marry James Murdock. It’s possible that our Nancy was not the blood daughter of John and Nancy – possibly a cousin.

John and Nancy moved their family to Russell County, Virginia in 1831 or 1832. They are on the 1840 land tax list for Russell County. The 1850 Census finds them in a part of Russell County, Virginia, Nancy’s home county, that is now Wise County near the Kentucky border. It’s believed that they settled on Sandy Ridge. Their son, John Ritchie, lived directly behind the little settlement of Cranes Nest at Fullers Gap on Cranes Nest River.

Fuller Gap viewed from Fuller Rocks

They were all in Wise County when it was formed. John Ritchie was a farmer and Nancy Hutchinson was a midwife.

John, Sr. died before 1860. Nancy appears in the 1860 Census as living near the Wise County Courthouse.

Nancy Ritchie married James Murdock before 1841 and lived in Iredell County, North Carolina.

A story is recorded in Singing Families of the Cumberlands by Jean Ritchie where descendants of John Ritchie and Crockett Ritchie accidentally met.

During the Civil War, two of John’s daughters would travel across the state line to Kentucky to peddle goods. On one such trip, they began talking to two Kentucky girls. After an exchange of names, they discovered that they were cousins, the two Kentucky women being the daughters of Crockett Ritchie, Long John’s brother. Long John’s daughters invited Crockett’s daughters to visit. As they began planning the gathering, they discovered a small problem. Long John’s family was on the Union side, despite being located in Virginia, and Crockett’s family was on the Confederate side. After promises of protection by the Virginia Ritchie family, the gathering was arranged.

As a personal note, though I related the story above as it was given, I rather think the women who met in Kentucky were more likely granddaughters of Long John and Crockett. It seems the actual daughters of these two men would have been too old for that kind of duty during the Civil War. They all would been in their late-40s to 50s at the time. In any case, it would have been nice to discover a description of the reunion when it happened.

Nancy Ritchie was buried in St. Michael’s Cemetery in Troutman, Iredell County, North Carolina. Perhaps one day I can tell more of a story about her life with James Murdock. In the meantime, I earlier prepared an essay about her son, John Franklin Murdock, from whom we are descended, in John Franklin Murdock – Another mid-19th Century North Carolina Life.

Background on the Keiths

From what I can see, there seems to be general agreement among Keith researchers that the immigrant ancestor of this Keith line was Cornelius Keith and Elizabeth Johnston. Cornelius was born before 1695. Many record his place of birth as the Loch Lomond area of Scotland because Loch Lomond, Stirlingshire is inscribed on a tombstone erected for his son, Cornelius, in South Carolina. Others assert that the location inscribed on the tombstone may have been in error.

Cornelius and Elizabeth emigrated with one son, Cornelius (Jr.), who was born in 1715 in Scotland. They are believed to have emigrated about 1720.

Clan Keith was an important supporter of the Jacobites in the 1715 Rising in Scotland. The  defeat of that rising led to the Keith chief having lands and titles forfeited. The chief’s family left Scotland for Europe, and the clan members began to scatter as did many other Highlanders in the years after the collapse of the rebellion. These may have been the circumstances that led Cornelius Keith to leave Scotland.

defeat of that rising led to the Keith chief having lands and titles forfeited. The chief’s family left Scotland for Europe, and the clan members began to scatter as did many other Highlanders in the years after the collapse of the rebellion. These may have been the circumstances that led Cornelius Keith to leave Scotland.

Cornelius is named, along with William Byrd, Captain James Terry and John Kendro, in a land grant of 1721 in the County of New Kent, Virginia.

In Virginia, Cornelius and Elizabeth had at least two more sons, John, born 24 December 1724 in Bristol Parish, Dinwiddie County, Virginia, and Samuel, born 13 December 1725, in Botetourt County, Virginia. Some genealogies show two more sons, Gabriel and James, in this list of siblings. And there may have been other children as well.

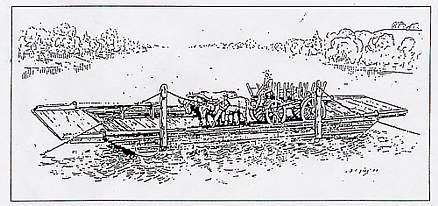

Cornelius, Sr. was living in Brunswick County as early as 1725, and there is a 1728 account of Cornelius Keith living on the Roanoke River, with a wife and six children (recorded in the Journal of William Byrd). Also in 1737, Cornelius was granted license to operate a ferry crossing on the Roanoke River, from his own landing. His land there was sold in 1742.

Sketch of a typical 18th Century Ferry

Cornelius Keith was also a mill stone maker. In Colonial America millstones were

Millstone Path at Hermitage Museum, Norfolk, Virginia

originally imported, but eventually they came to be quarried in the colonies. A millstone that was five to six feet in diameter and weighed between one-and-a-half and two-and-a-half tons might have been good for twenty years. Flint and buhrstone were the most common materials used in Virginia, while quartzite was more common in North Carolina. We assume Cornelius used one or more of these materials.

Our line descends from Samuel Keith, who married Catherine Ring (born about 1730) . They had four children, Henry (1750) and Reuben (about 1754), both born in Buncombe County, North Carolina, and Gabriel (about 1755) and Mary “Polly” (1758) in Botetourt County, Virginia.

Some researchers show Gabriel as Catherine Ring’s husband. Others show Samuel. It is conceivable that Gabriel married his brother’s widow. The year of Samuel’s death is a little uncertain.

There are two interesting stories involving the Keiths that I relate below.

Cornelius Keith Arrives In Cherokee Land

Cornelius Keith, Jr., my 7th great uncle, was born in 1715 in Scotland, possibly in the Loch Lomond, Stirlingshire area. When he was still a child, he came with his parents to Virginia and settled on the Roanoke River in Brunswick County. He married Juda Thompson, then Mary (or Sarah) Bohannon. As a side note, “Bohannon” is simply a different anglization of “Buchannan.”

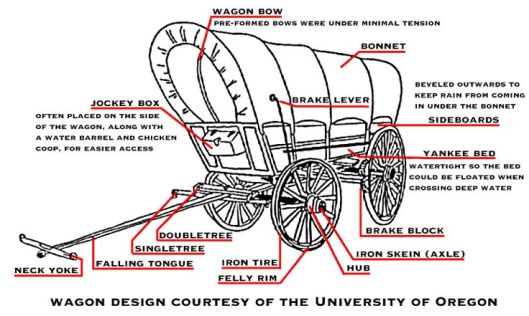

There was a great deal of movement in the colonies in the mid-18th century as settlers migrated looking for cheaper land. In 1743, Cornelius and his family moved southward along the Blue Ridge mountains in a narrow-gauge covered wagon pulled by a pony with two other ponies hitched to the back of the wagon.

A typical family would have filled that wagon with clothing, bedding, dishes, dried vegetables and fruits, and breadstuffs enough to last for months until more could be made. There would have been grain and other seeds for planting, a spinning wheel, tools, iron pots, kettles, ovens, and buckets.

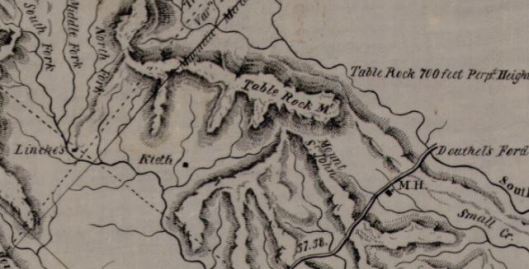

They probably followed the Indian trails and blazed the way close to the hills of the Blue Ridge Range. They came down into the Carolinas and finally settled in the uplands of South Carolina in what became the Oolenoy Community in Pickens County, South Carolina in view of Table Rock Mountain.

They probably initially built a brush harbor on a flat-top hill overlooking the Oolenoy River Valley and the surrounding mountains. I read that Miracle Hill Mission School is now located on this ground and has a plaque memorializing the original settler, but I have not seen a picture of the plaque.

Sketch of a brush harbor church. A home would have been closed on all sides with brush and stick or canvas flap for a door

There was a Cherokee village on Uwharrie Mountain and these were the first first white settlers in their territory. However, it didn’t escalate into conflict. Keith and the Cherokee Chief Woolenoy bartered. Keith told Woolenoy he would trade one pony for land and asked how much land he would give. The chief showed that he would give all the land

Oolenoy River

Keith wanted. So, Keith traded the pony for a big wedge of what is now Pickens County consisting of the entire lower half of the Oolenoy River Valley and for the privilege of hunting and fishing. Family lore says that this trade was sealed by the ceremony of smoking the peace pipe. This was the beginning of the Oolenoy Settlement.

Uwharrie Mountains

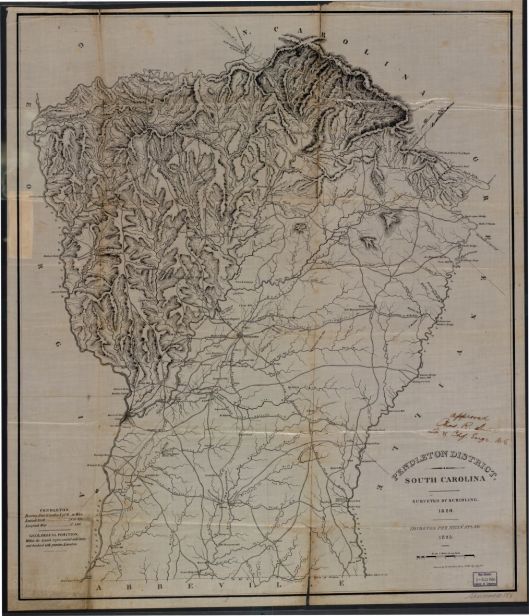

The below Mills Map of the Pendleton District, published circa 1825, has the word “Keith” on the spot where Cornelius Keith built his first hut.

The first Keith cabin was probably one room with a dirt floor and stick and dirt chimney. The cracks would have been chinked with mud to keep out the cold. Long boards were rived from trees of the virgin forest for the roof, door, and window shutters. Later, a puncheon floor was added and a shed room.

The relationship with the Cherokee helped the family survive the first year and learn to thrive in this area.

Keith researchers say that as the family grew a large log house was built with two large rooms with an open hall between. Steps went from this hall to two upstairs bedrooms. There were also two shed rooms at the back. The chimneys were of field rock with mud mortar.

They raised twelve children on this land, three of whom served in the Revolutionary War although the Cherokees were in sympathy with the British. Given the positive relationship between the Keiths and the Cherokees this must have been quite a story.

The younger son of the chief of Clan Grant, Ludovic, was sentenced to transportation to the American Colonies for his role in the 1715 Rising. After spending seven years of indentured servitude, Ludovc Grant ended up living among the Cherokee of North Carolina, even marrying a Cherokee woman and remaining with the Cherokee Nation for decades until his death. Given their relationship with the Cherokee and being Scottish Highlanders, I wondered if the Keiths came to know Grant, but have not found any such indication.

Cornelius Keith died in 1808 and was buried in Oolenoy Church Cemetery. His monument was patterned after that of an Indian chief — a mound of field rock with a small soap stone head rock. The inscription was simply, Cornelius Keith, Born 1715, Died 1808. In 1956, his descendants erected a monument which contained a bronze plaque with the Keith Coat of Arms.

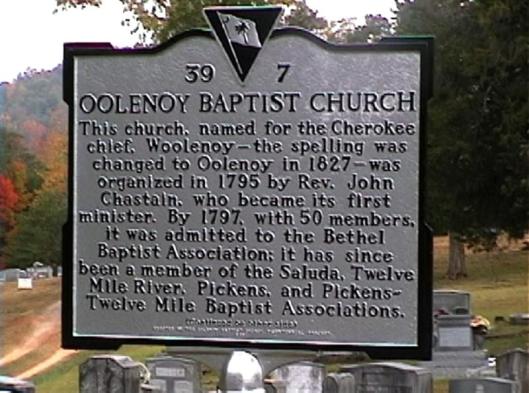

Oolenoy Baptist Church – An integrated church

The story of the Oolenoy Baptist Church graveyard where Cornelius was buried is another interesting story of the South.

The story of the Oolenoy Baptist Church graveyard where Cornelius was buried is another interesting story of the South.

After the Revolutionary War more people moved into the area of the Keiths. After 1795 enough settlers were present to warrant a church being built. By the time other Keoth brothers had joined Cornelius on his land. They jointly provided land for a small log church roofed with wide boards split from white oak trees. It was not heated so services may have been discontinued in the winter. The first pastor and organizer of the church was Rev. John Chastain. Church records do not exist before1833. in 1834, the church was called “The Church of Christ”. Despite its presence in the South, the church was multi-racial. In 1837, two Blacks were received by letter. The 1845 minutes report 97 members, including 18 blacks. Black participation in the church continued until Black families left the area after 1868. A new building of planks was built in 1840. This church was larger than the old one – about 40 feet long. It had big windows with wooden shutters. The floor and seats were made of rough planks.

And there we leave it for now – two Scottish Highland families, both affected by 18th century wars, the 1715 Rising for the Keiths and the 1745 Rising for the Ritchies, and both searching for new lives in the American colonies, ultimately bonding their families through marriage in yet another Southern story of our family.

I have enjoyed the reading journey, thank you.

To my sheer surprise and fascination; I have recently discovered that Cornelius Keith (B 1715) was in fact my 5th Great Grandfather. Wow!